It is time to talk about the Product Owner, a role that most people developing solutions do not understand. Let us start by pointing out the the Product Owner as a role has NOTHING TO DO with developing solutions. It is a role independent of methodology or process. If a company sells products or services, then it has Product Owners, no matter what they may be called.

So what is a Product Owner? A Product Owner is a person in a company responsible for making sure that a product or service offered by the company is as profitable as it can be (or that it is time to end-of-life the product or service if it is no longer worth maintaining). As a start, a Product Owner knows intimately what the product or service is about, what the market is for the product or service, whether the market growing or contracting, why the customers care about the product or service, what else the customers are looking for, who has competing products or services, and who has complementary products or services. The Product Owner has a continuous task of market research and analysis.

You could say that the Product Owner is the ultimate subject matter expert on the product or service – not in the sense of how to use it, but in the sense of what it is for, what problems it solves, and the market it is in.

Examples of products and services that would have a Product Owner include:

- Adobe Photoshop

- Microsoft Word

- Personal checking accounts offered by your bank

- Term life insurance offered by your insurance company

- Personal shopping service for busy executives at a major department store

- Purina Hamster Chow

- Ever Ready Batteries

- Facebook timeline

Depending on the size of the company, the Product Owner may be even more specialized, such as the Product Owner for Term Life Insurance for people over 45.

Like a homeowner with a list of projects to do around the house, a Product Owner will have an ever changing list of things he or she wants that will improve the product or service. The list may be in the Product Owner’s head or, even better, in a spreadsheet or database. A good Product Owner will review this wish list periodically to see if it needs to change based on changes in the marketplace. This is the same kind of thing a homeowner does; you may have a list of projects based on the idea of living in the house for the next 20 years, when suddenly your spouse gets a job offer too good to refuse in another state, and you change the list of projects to match the goal of selling the house.

No Product Owner I have ever heard of has unlimited funds to do whatever he or she wants with their product or service. Periodically, let’s say every 6 months, a Product Owner selects the things that are most important about the product, and writes a proposal for developing a solution for those things. In order to convince the upper level decision makers that his/her ideas are the best, the Product Owner puts an expected value on the things he/she wants to develop, along with an expected cost for developing the solution.

For just a few ideas, a Product Owner may want money to:

- Develop a strategic partnership with a company with complementary products

- Divide a product into basic and advanced versions to answer the complaints of 80% of the customers who say it is too complicated, while not losing the expert market

- Add features highly requested by customers

- Add features that research shows us are the things that are causing our customers to buy the competitor’s product instead

- Fix some bugs that have been discovered since the last funding cycle

This proposal of what to do along with an expected Return on Investment (ROI) is typically reviewed by a corporate portfolio committee. This portfolio committee’s job is to find the things of highest value for the company overall and fund those endeavors. This is a challenging task, since many things have to be considered. Some of the selection criteria may include the things that will make the most money, the things that will save the most money, or the things that modernize failing infrastructure. This committee often has separate pots of money for different things that are important to the company, such as ongoing maintenance, research and development, new products, upgrades, and regulatory. This way they are comparing for example two ongoing maintenance proposals to each other, and not trying to compare ongoing maintenance with research and development proposals.

Some companies have a different funding process, where the product is funded for some period, often a year. The amount of funding for the product is based on past earnings, projected earnings, value to the company compared to other products, and corporate direction. In this situation, the Product Owner has the authority to decide what to spend the money on throughout that period.

Hooray! The Product Owner has money to do the work. Now what? Well now he/she needs a better idea of what it will take to develop a solution, so that the right people can be brought on board to do the work.

The Product Owner now divides the work into work packages. A work package is a relatively small, independent bit of work. The Product Owner will often work with other people to write up the work packages, people who are familiar with what it will take to develop a solution. Done well, one work package can be assigned to one group of people to implement, while another work package is assigned to a different group of people to implement. This allows for the complete solution to be developed in parallel, thus getting the solution to market faster.

At this point, the Product Owner has some decisions to make. First, are all the work packages equal, or does it matter which is completed first. The Product Owner may say that as long as everything is delivered in 6 months the order does not matter. Or the Product Owner may recognize that it would be a large advantage in the marketplace for some of the work packages to be delivered earlier. Or perhaps some work packages describe areas of risk that the Product Owner would like to have developed first, so that he/she can send out the early solution to targeted customers to get feedback before the final product is released. What I have just described is Release Planning, where the Product Owner is making business decisions on what will be released and when.

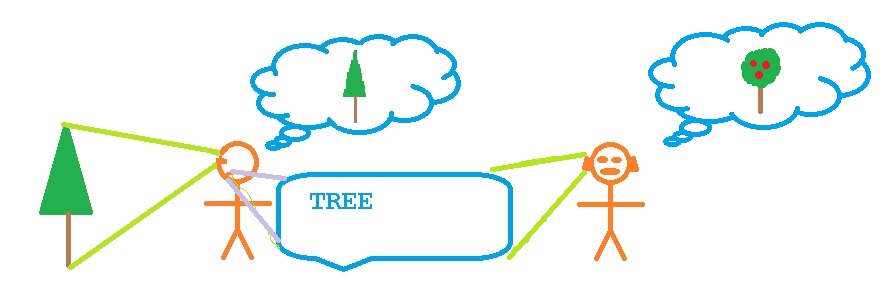

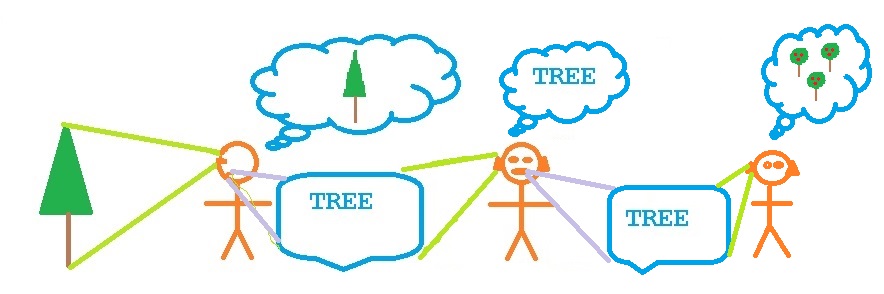

Another decision the Product Owner has to make is does he/she want to write all the detailed requirements up front and hand them off, or does he/she want a person to represent the requirements to the team developing the solution. This is the fundamental difference between Waterfall and Agile development processes; a document containing requirements or a person representing the requirements. If the Product Owner chooses to have a person work directly with the solution delivery team, this may be to address areas of uncertainly that the Product Owner expects will change. Most Product Owners do not have the time to sit with the solution delivery team day by day, so he/she will delegate someone else to do that work. The delegate is responsible for keeping in close communication with the Product Owner.

The Product Owner needs to be very clear on his/her expectations regarding status reports and demonstrations of progress. The Product Owner also has to be very clear who gets to make what decisions throughout the solution development.

You may notice I have worked very hard to avoid mentioning software. Software is one kind of solution, but may not be the whole, or any part of the solution. If the Product Owner is developing a strategic alliance with a company with complimentary products, there may not be any software developed, and yet this endeavor is expected to bring value to the company. Or the solution may involved hardware and firmware. Or the solution may be to hire a vendor to come and install an upgrade to their product.

Product Owners are very important for the health and profitability of the company. We make a mistake if we only think of them as people who supply the requirements for our projects.